CFIUS Non-Notified Transaction Enforcement: Cooley’s Five-Year Lookback

March 2025 marked the fifth anniversary of the Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States (CFIUS) initiative to “formalize and centralize” within the Department of the Treasury an enforcement function to identify and investigate “non-notified” transactions (i.e., cross-border acquisition and investment transactions that may have been subject to CFIUS jurisdiction but not formally “notified” to CFIUS for review). In support of this enforcement push, the Department of the Treasury “has dedicated staffing, training, resources, and outreach to support this critical effort—strengthening and sharpening the Committee’s ability to identify and assess whether non-notified transactions merit further review.”

This article discusses our firm’s experience with non-notified CFIUS inquiries since the beginning of the 2020 enforcement initiative, and reports the trends, outcomes and government practices we have observed in our matters.

Introduction and overview

The data discussed below were gathered from the non-notified inquiries we handled between 2020 and 2024. These data include certain information and trends not disclosed by CFIUS in its annual reports to Congress or other public announcements – including the passage of time between transaction close and the issuance of a non-notified inquiry, the percentage of “TID US businesses” involved in a non-notified inquiry, the number of rounds of questions and answers involved in an inquiry, and the time lag between CFIUS’s receipt of responses to CFIUS questions and CFIUS’s issuance of follow-up questions.

While our experience is certainly not the whole picture, we estimate that the 50 non-notified matters from which we draw our data constitute more than 10% of total non-notified activity for the period, and therefore may be generally representative of non-notified dynamics over the past five years.

For context, the 50 matters that constitute our data set represent about 2% of the 2,000+ matters we advised on during the relevant five-year period. Because our CFIUS practice focuses heavily on venture financing transactions, our data correspondingly tend to reflect CFIUS dynamics concerning “covered investments,” as opposed to “covered control transactions” (see 31 CFR § 800.211 versus 31 CFR § 800.210). Because our clients tend to operate and invest in the technology, artificial intelligence (AI) and life sciences industries, we also may see a disproportionate number of matters involving US businesses whose operations are generally of interest to CFIUS.

Before discussing the details, some general observations:

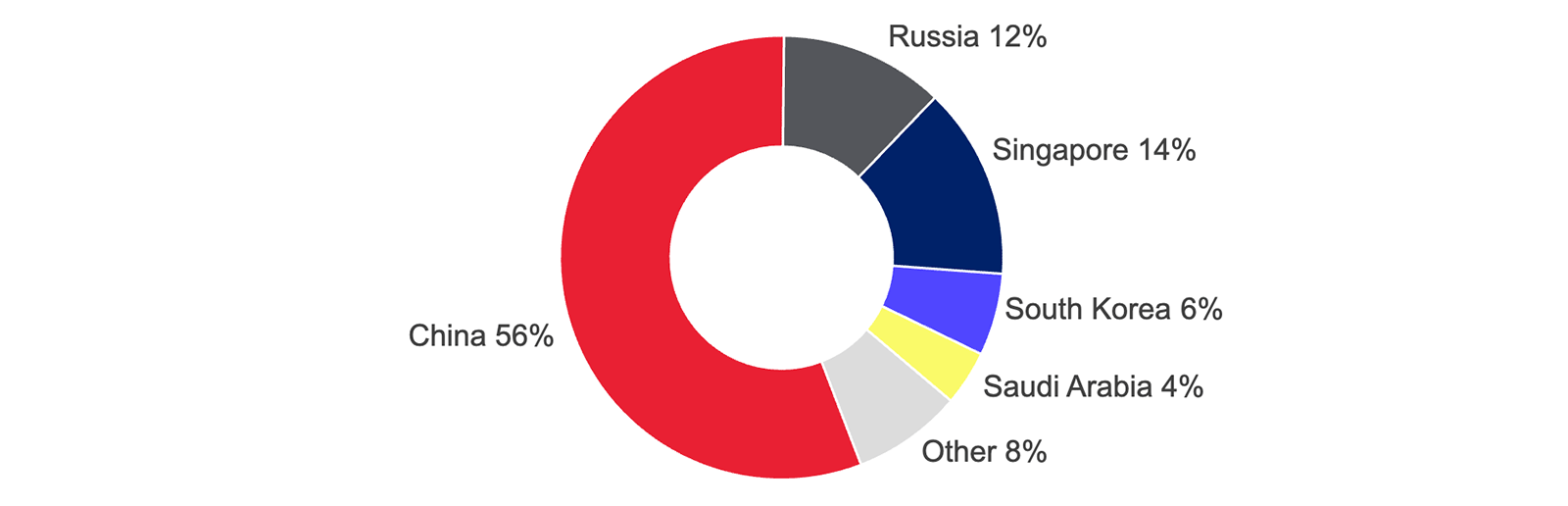

- As may be expected, our experience reveals a focus on investments from China, with about 56% of our inquiries involving Chinese investors. (Singapore placed second in our data, appearing in 14% of our matters.) We also observed a focus on US businesses that operate in industries generally perceived to present national security vulnerabilities (i.e., life sciences, cybersecurity, AI, semiconductors and battery technologies). In this sense, our data reflect non-notified outreach consistent with the policy motivations behind the Foreign Investment Risk Review Modernization Act (FIRRMA) and its implementing regulations.

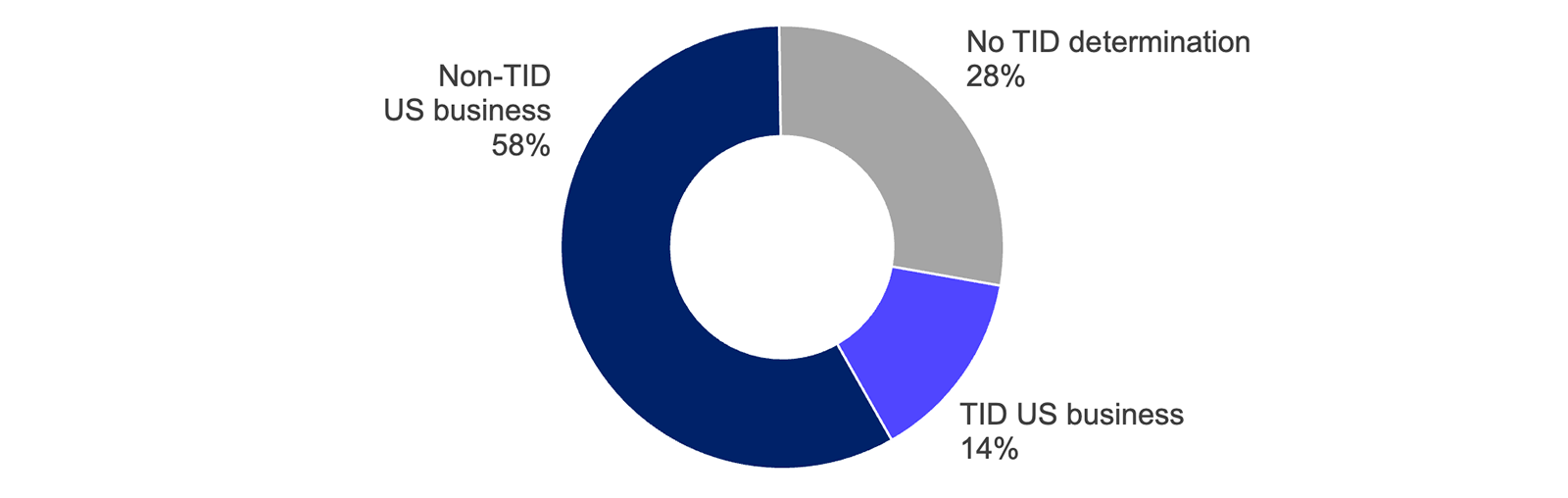

- Perhaps surprising however, is the proportion of “TID US businesses” to non-TID US businesses that CFIUS has targeted with non-notified inquiries. In our matters, most (i.e., 58%) of the US businesses did not deal in “critical technology,” “critical infrastructure” or “sensitive personal data.” We regard this statistic to indicate that a company’s “TID” status is a poor proxy for the presence of perceived national security vulnerabilities. This stands to reason, as many companies with “critical technology” (e.g., common encryption functionality in software) do not present colorable national security issues, whereas other companies (e.g., in the life sciences industry) may have sensitive know-how with national security implications, but no critical technology.

- Also notable is the size (measured by dollar value) of the transactions targeted with non-notified inquiries. Several of the transactions in our data set involved venture investments under $1 million. As with a company’s “TID” status, transaction size seems to be a poor proxy for the presence of national security concerns arising from a transaction. What is certain from our experience, however, is that non-notified inquiries can impose disproportionate burdens on small venture-backed US businesses. When a relatively small transaction is targeted with a non-notified inquiry, the cost of responding to CFIUS can represent a significant portion of the total transaction costs of the deal.

The data set

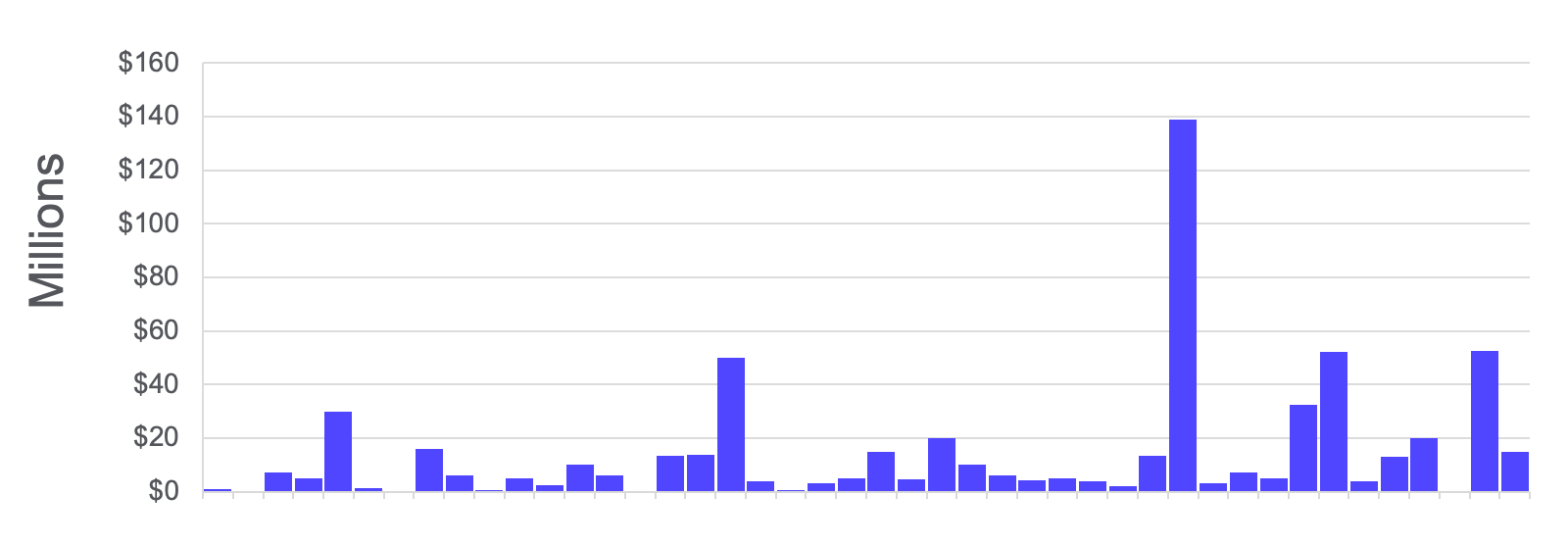

As we wrote in this September 2024 alert discussing CFIUS penalties and non-notified dynamics, CFIUS initiated inquiries into 396 non-notified transactions between 2020 and 2023. (CFIUS has not yet reported non-notified data for 2024.) As illustrated below, the annual share of all non-notified inquiries that we have handled has fallen each year since 2020 – from 15% in 2020 to 7% in 2023. The total number of non-notified CFIUS inquiries each year also has fallen since 2021, which saw more than twice the number of inquiries reported just two years later in 2023.

Non-notified inquiries by year

Investor nationality

While our data include non-notified inquiries targeting investments from around the globe, most (approximately 56%) of our matters involved foreign investors from China – including Hong Kong. Roughly a third of our matters (36%) involved investors from a small cohort of other countries – including Singapore (14%), Russia (12%), South Korea (6%) and Saudi Arabia (4%). The remaining 8% of our non-notified matters involved investors from Malaysia, Australia and the US.

Non-notified inquiries by investor nationality

At a superficial level at least, this picture seems to generally align with CFIUS’s policy priorities and with market expectations that Chinese and Russian investors are “high risk” for CFIUS purposes. The data also illustrate the reality that an investor’s “nationality” is not always evident from publicly available information or from other data available to CFIUS at the time a non-notified inquiry is initiated. (Hence the inquiries concerning US investors.)

Indeed, oftentimes transacting parties themselves do not have a clear understanding of how CFIUS would assess an investor’s nationality – including its “principal place of business” (a complex defined term in the CFIUS regulations) – or the nationalities of the entities and individuals that “control” the investor, thus imparting their own “nationality” to the investor. The complexity and uncertainty associated with CFIUS nationality determinations underscores the importance of conducting CFIUS diligence and thoughtfully allocating risk at the outset of a transaction (e.g., with appropriate representations and covenants).

US business industry sectors

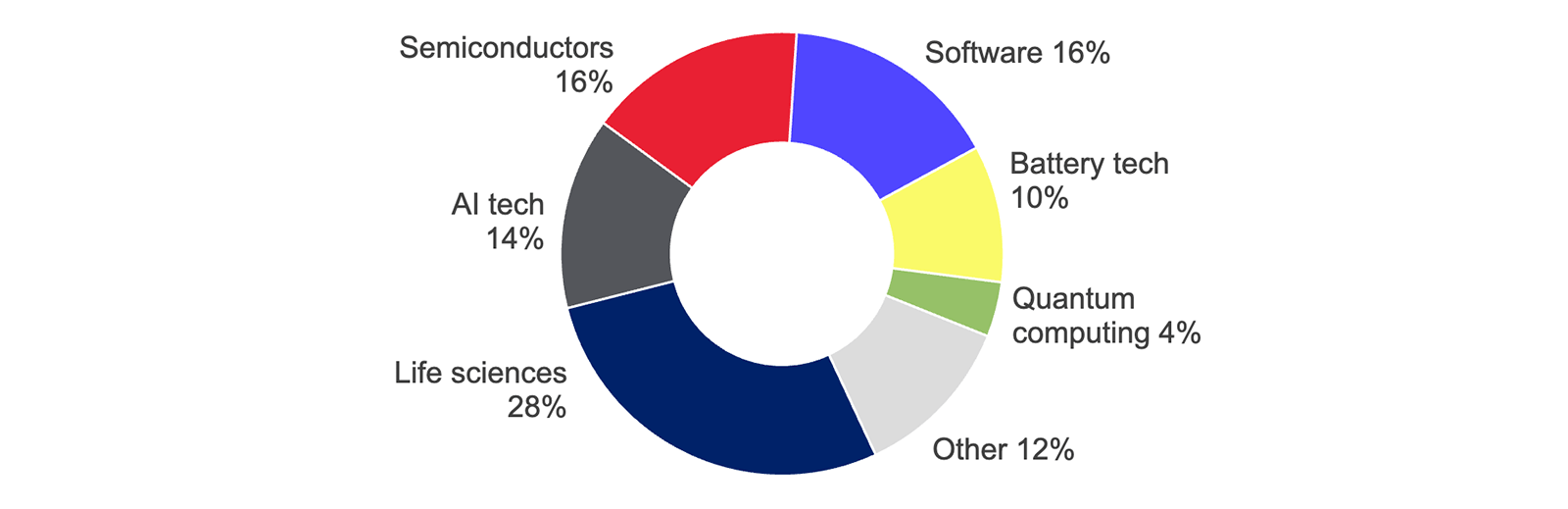

As CFIUS observers would expect – and in alignment with FIRRMA’s mandate that CFIUS focus on venture financings involving US companies that deal in “critical technologies,” “emerging technologies” and “foundational technologies” – our data confirm that Silicon Valley and other technology and innovation hubs represent a new center of gravity for US national security.

Overwhelmingly, the non-notified matters we have handled since 2020 involved US businesses in the life sciences (28%), software (16%), semiconductors (16%) and AI (14%) sectors. We also have seen multiple non-notified inquiries targeting investments in the battery technology (10%) and quantum computing (4%) sectors. Only 12% of our non-notified matters for the past five years did not involve a US business in one of the six industry categories depicted here.

Non-notified inquiries by US business industry

Even more than investor “nationality,” the industry in which a US business operates appears to be a fair indicator of the probability of receiving a non-notified CFIUS inquiry. While we have seen CFIUS reach out to companies that were perhaps later determined not to present national security vulnerabilities, on balance, it seems clear that CFIUS is able to determine on the basis of publicly available information whether a non-notified transaction warrants an inquiry.

Focus on ‘TID US businesses’

Consonant with the policy objective of reaching more venture-style foreign investments, FIRRMA establishes a lower CFIUS jurisdiction threshold for investments in US businesses that deal in “critical Technologies,” “critical Infrastructure” or “sensitive personal Data” (so-called TID US businesses). This emphasis on TID US businesses reflects a judgment that such companies are more likely than the average business to present susceptibilities to the impairment of national security. While this may be a reasonable judgment, in practice we see many examples of non-notified inquiries targeting companies that are not TID US businesses.

Our data reveal that TID US businesses were present in a significant minority of non-notified outreach. Among the 50 inquires in our data set, we made a positive TID determination with respect to fewer than 15% of matters. The majority (58%) were determined not to be TID US businesses, and we made no determination with respect to 28% of the businesses targeted. (When no determination was made, the circumstances of the transaction typically indicated a clear absence of CFIUS jurisdiction, thus obviating the need to conduct a TID analysis.)

While these figures may seem counterintuitive, they make sense in the context of the regulatory definitions of “critical technology,” “critical infrastructure” and “sensitive personal data” – the three elements of a TID US business. As noted, many companies write software code that constitutes “critical technology” (because the code leverages encryption functionality subject to export controls), yet do nothing implicative of substantive national security issues. Conversely, many companies – in the biotechnology sector, for example – work with sensitive technologies but do not themselves “produce, develop, test, manufacture, fabricate, or design” the controlled toxins or pathogens that constitute “critical technology” under the regulations. Viewed through that lens, it should be no surprise that non-notified inquiries often land with non-TID US businesses.

TID US business status

This reality underscores the importance of understanding both the relevance and limitations of company-side CFIUS diligence with respect to “TID” status. Whether a company is a TID US business can inform an assessment of national security vulnerabilities, but is not dispositive of CFIUS risk.

Oftentimes, the more important consequence of a company’s TID status is with respect to CFIUS jurisdiction assessments. In the context of a financing transaction, parties that are confident that the company is not a TID US business have more flexibility to shape the terms of their transaction without triggering CFIUS jurisdiction (i.e., they can afford a foreign investor board rights and shares in excess of 10% without necessarily crossing a “control” threshold). Conducting and memorializing a TID analysis also can position parties to quickly address non-notified CFIUS inquiries by establishing the absence of CFIUS jurisdiction to substantively review a transaction post-closing.

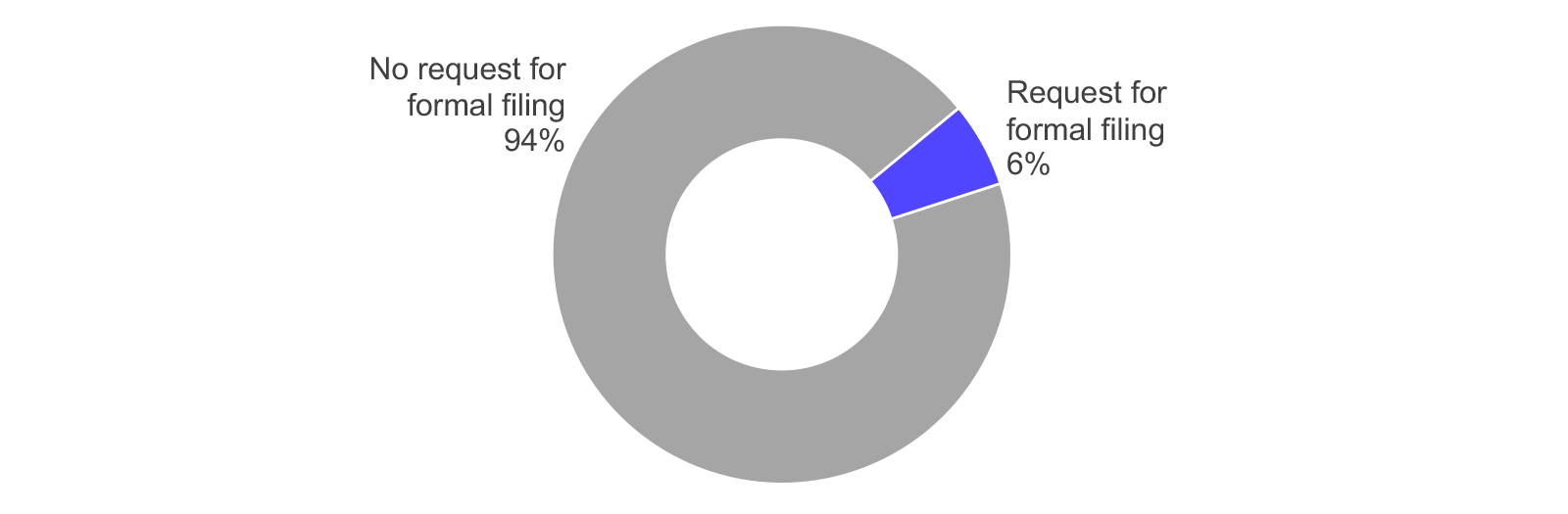

Formal filing requests

With this in mind, parties can structure transactions to limit foreign investors to truly passive positions, thereby insulating themselves against CFIUS jurisdiction while also guarding against substantive national security risks. When parties negotiate and memorialize limitations on a foreign investor’s ownership interests and governance and information rights, and act in accordance with those limitations, they protect themselves from costly government inquiries and support the national security policy priorities that FIRRMA seeks to implement. With the cautionary note that it is never sufficient or advisable to simply “paper the file” (e.g., with a side letter limiting investor rights) to shield a transaction from CFIUS jurisdiction, parties that genuinely can structure and enforce passive investment dynamics will be well positioned to resolve a non-notified inquiry by disclosing their transaction terms transparently to CFIUS. Among the 50 transactions in our data set, only three (6%) resulted in a formal filing with CFIUS.

Transaction size

In the age of FIRRMA, it should be axiomatic that transaction size is not necessarily indicative of the perceived national security implications of a foreign investment, and our data bear that out. While there may be a positive correlation between large transactions and perceived national security risk, the inverse is not true of “small” transactions – particularly in the venture financing space. In our sample of 50 non-notified inquiries, seven matters involved transactions valued at less than $1 million, and 23 were valued at $5 million or less. Two transactions were valued at about $200,000 or less, and only five were valued at more than $30 million. (For six of the matters in our data set, the transaction value was unascertained or unascertainable for various reasons.)

Transaction size

These data illustrate the reality that CFIUS may initiate non-notified inquiries without regard to or knowledge of the size of the transaction at issue. For transacting parties, the message is clear: Small financings that otherwise have the superficial attributes in which CFIUS takes an interest (e.g., apparent investor nationality and US business industry sector) are not insulated from CFIUS risk, and appropriate diligence and planning is always warranted.

CFIUS process dynamics

If there is a universal complaint among transacting parties targeted with a post-closing inquiry, it is with the CFIUS non-notified process, which is costly and often characterized by uncertainty, imbalance and a lack of finality that can seem inconsistent with fundamental legal principles.

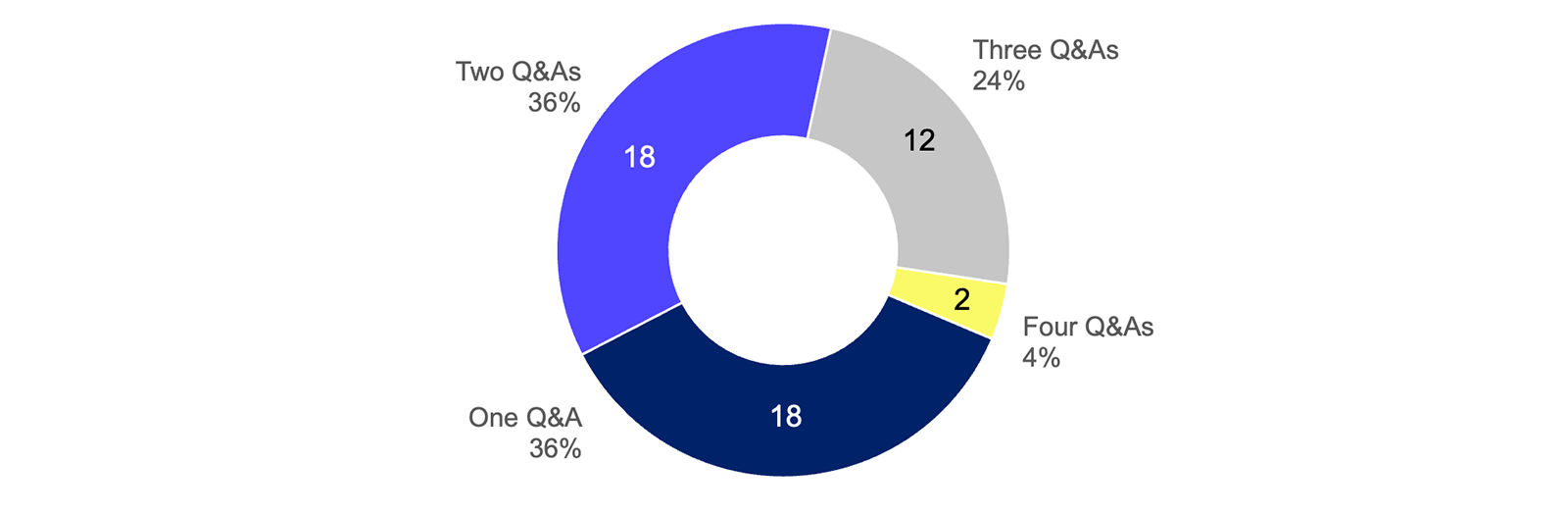

Non-notified Q&A process: The primary cost driver of a non-notified inquiry is the “question and answer” regime pursuant to which CFIUS determines whether it has jurisdiction to require the parties to file a formal CFIUS notice. Among our matters, nearly all (96%) involved between one and three “rounds” of questions and answers.

Number of Q&A rounds

While that may not sound unduly intrusive, in practice, the Q&A process often proves to be quite burdensome. For context, recall that CFIUS’s authority to ask questions in the non-notified context has historically been narrowly limited to ascertaining whether a transaction is subject to CFIUS jurisdiction – as assessment that should be addressable with relatively few questions, appropriately drafted. CFIUS observers will note, however, that notwithstanding that narrow scope, CFIUS often asks questions touching on the national security implications of a transaction – e.g., the specific nature of the US business’s customer relationships with the government and government contractors. While such questions are arguably "out of bounds," parties and their counsel are nonetheless often inclined to answer them for a variety of reasons – a dynamic that tends to increase the burden of the non-notified process. (Note that new rules recently expanded that scope of authority to officially permit CFIUS to ask questions broadly relating to the national security aspects of a non-notified transaction – a rule that can be expected to lengthen the non-notified process and correspondingly increase costs to transacting parties.)

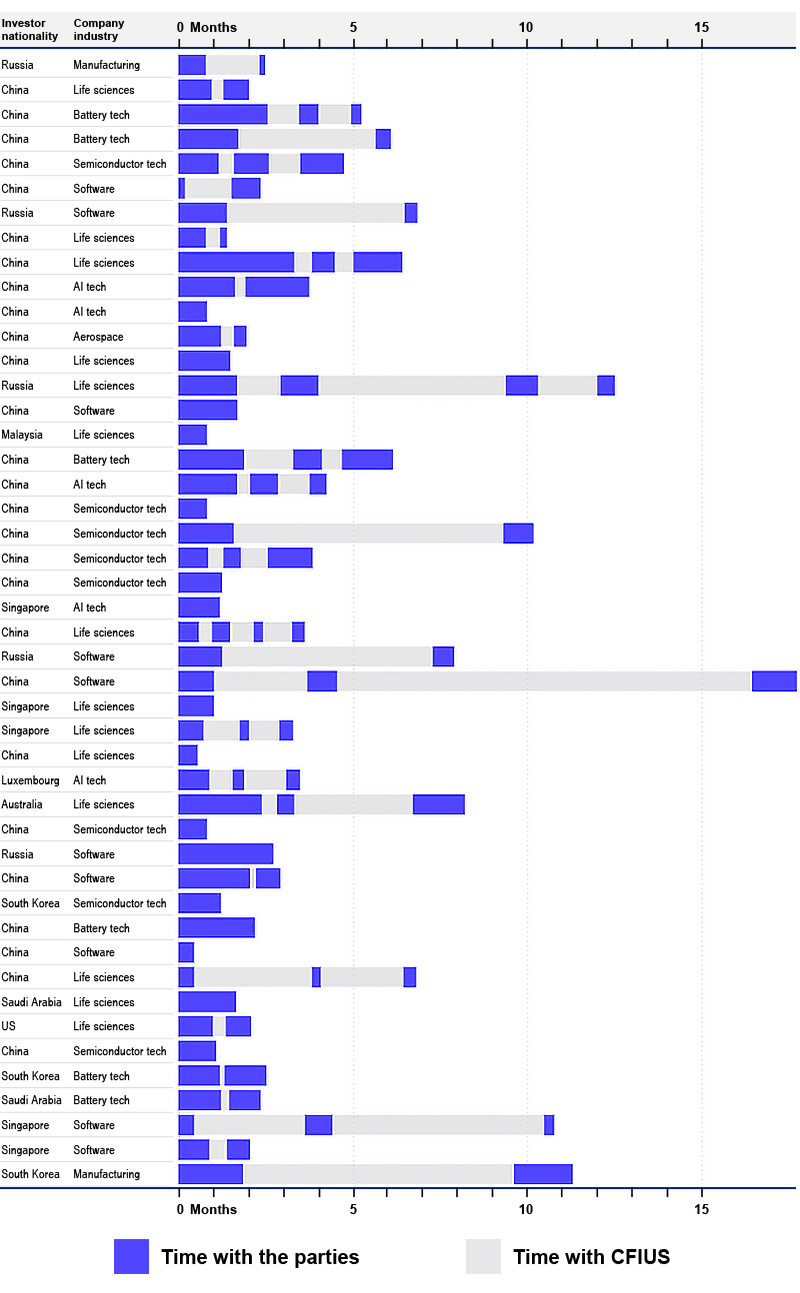

Q&A response cycle dynamics: Parties have similar complaints about the perceived imbalance with respect to the time afforded to the parties to respond to CFIUS questions and the time CFIUS itself can take to digest those responses and return to the parties with more questions. As the table below illustrates, CFIUS often returns with additional questions months – and in one of our matters, a full year – after receiving responses to its prior questions. In the illustration below, the periods shaded in blue represent the time the parties spent assessing CFIUS’s questions and preparing their responses, and periods shaded in gray represent the time that CFIUS spent with those responses before issuing new questions. Our data reveal five instances (10% of our matters) in which CFIUS returned to the parties with additional questions more than six months after receiving the immediately preceding responses. (Note that this chart lists only 46 matters; the remaining four matters in our data set were resolved without the necessity of a formal Q&A exchange.) For transacting parties, this imbalance and unpredictability can have a chilling effect on post-non-notified fundraising and relationships and is generally disruptive.

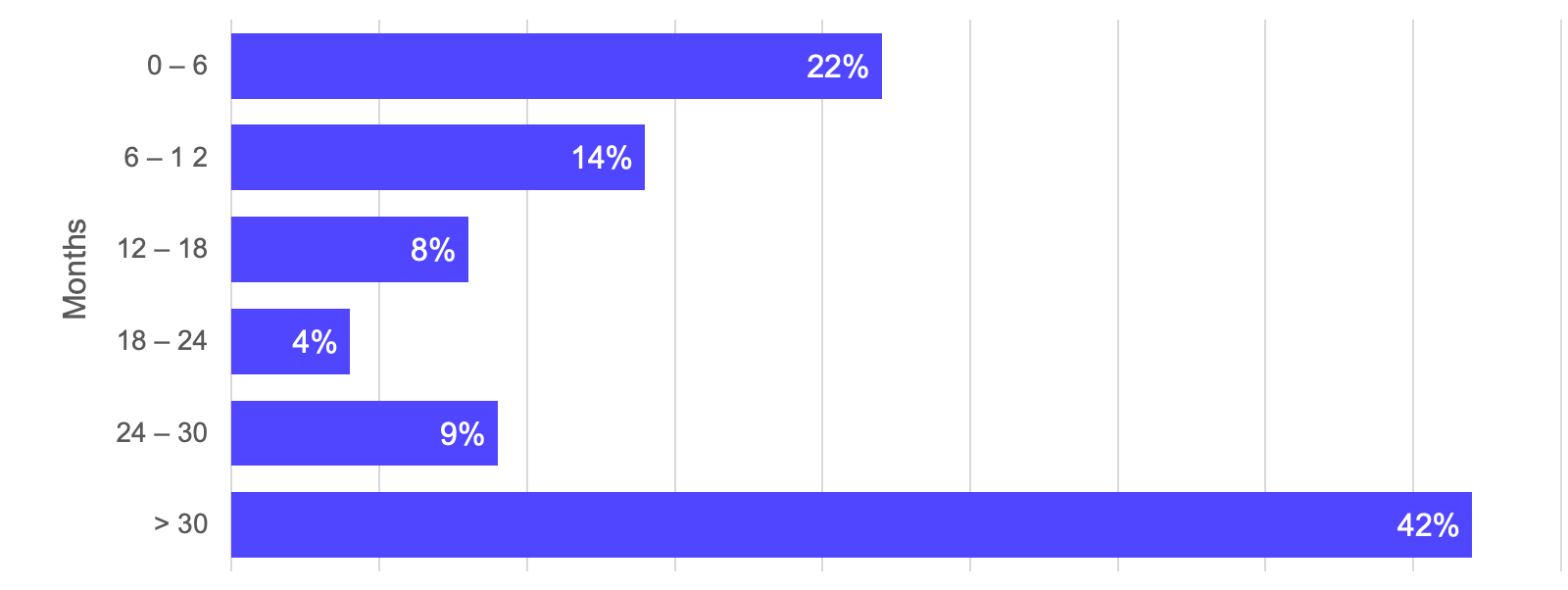

Inquiries regarding old transactions: Also vexing is the amount of time between the date a transaction closes and the date CFIUS issues a non-notified inquiry. In our matters, only about one in four non-notified inquiries (24%) were issued within six months of the transaction closing. Most commonly (in 39% of matters), the CFIUS inquiry arrived more than two-and-a-half years after closing. These delays may shorten over time (e.g., to the extent they reflect CFIUS’s efforts to clear a backlog of transactions that the non-notified office has been working through), but for the parties involved, receiving a CFIUS inquiry years after a transaction closes can create an unexpected hardship.

Months between transaction closing and non-notified CFIUS outreach

Lack of finality: Perhaps the most common complaint with the non-notified process is the lack of finality with inquiries. CFIUS does not issue closing letters or otherwise inform transacting parties that a non-notified inquiry is “closed” or “resolved” as it does with voluntary and mandatory CFIUS filings. While this practice presumably gives CFIUS flexibility to keep a file “open” to revisit in the future, from the parties’ perspective, the lack of finality leaves a sword of Damocles above their heads in perpetuity. Practically speaking, no US business that has received a non-notified inquiry (except those that have been asked to file a formal CFIUS notice) can represent to investors or customers that the inquiry has been “resolved.” If CFIUS were to change anything about the non-notified process, many companies and investors would put finality determinations at the top of their wish lists.

Other anomalies

Other anomalies with the non-notified regime seem less impactful to the transacting parties and likely could be resolved with relatively minor process adjustments. For example, in our experience, CFIUS sometimes asks the same questions multiple times across multiple question sets. This adds to the cost of compliance and threatens to undermine public faith in the process. Improved coordination inside the non-notified office likely could eliminate duplicative questions without compromising the government’s legitimate interest in making jurisdiction and national security risk assessments, while respecting the transacting parties’ legitimate interest in preserving funds for shareholders and business purposes. (Another explanation for repeated questions may be the perceived failure of the parties to answer the initial question in the first place – in which case the fault may lie with the parties, and not with coordination within the government.)

Conclusions and recommendations

“Non-notified” inquiries have become increasingly common since the implementation of FIRRMA reforms, and we can expect currently-pending changes to the non-notified regime – including new authority to ask questions relating to national security risks, new subpoena powers and increased penalties – to increase the burdens on parties involved in an inquiry. While there is little that transacting parties can do to avoid a CFIUS inquiry, there are steps they can take to prepare for the process and minimize the burdens of responding to an inquiry.

- Conducting appropriate CFIUS diligence: Parties should develop a plan to conduct and memorialize appropriate CFIUS diligence in each transaction. Best diligence practices include assessing a company’s “TID US business” status and identifying all “foreign person” investors involved in a transaction. Making these determinations early in diligence can give the parties the necessary time and information required to manage CFIUS risks. Once these fundamental factual determinations are settled, parties can decide whether further CFIUS diligence (assessments of national security risks that inform voluntary CFIUS filing decisions and the likelihood of a non-notified inquiry) is warranted based on their risk tolerance and transaction timeline. Having a written record of diligence determinations can be helpful in the event CFIUS asks the parties to share their determinations regarding TID status and jurisdictional questions.

- Managing CFIUS risk: Armed with appropriate diligence, transacting parties can negotiate appropriate CFIUS representations and covenants and make appropriate transaction structuring decisions (e.g., requiring certain investors to be passive or limiting equity ownership levels) to manage the impact of a non-notified inquiry. Memorializing diligence findings, preserving documentation of those findings and the parties’ rationale for transaction decisions can facilitate efficient and accurate communications with CFIUS – even long after a transaction has closed.

- Negotiating other key terms: Because non-notified inquiries often require input from both parties to a transaction, it can be prudent to anticipate and negotiate terms to address commercial implications of an inquiry. For example, many parties negotiate covenants to cooperate in the event of a non-notified inquiry to ensure accurate and relevant information is provided to CFIUS. Some parties agree to indemnification provisions or to taking specific actions (e.g., automatically terminating certain investor rights) upon receipt of an inquiry. Because there can be potential disadvantages to such agreements, however, careful thought should be given to such terms.

- Setting expectations: Understanding the non-notified process and its potential implications for companies and investors can help decision-makers (e.g., company and investor management) and other stakeholders (e.g., company customers and third-party investors) set reasonable expectations regarding non-notified inquiry dynamics. The data points and trends discussed above should be part of an informed approach to CFIUS risk. Parties also may find the following observations from our matters helpful to consider:

- While an investor’s nationality is a reasonably good predictor of non-notified risk, CFIUS does issue non-notified inquiries with respect to transactions involving investors who are not generally considered high-risk. Because investor nationality is not always readily evident, appropriate diligence is warranted.

- The industry in which a US business operates and the technology it develops is probably a better indicator of post-closing CFIUS risk than investor nationality. Unlike nationality assessments, it is often relatively easy to assess a company’s business model and technology for CFIUS risk.

- A company’s status as a “TID US business” is relevant to a CFIUS risk assessment, but not dispositive of the likelihood of receiving a non-notified inquiry. Critical technology, for example, often manifests in companies that present no discernable national security vulnerabilities.

- Transaction size tends not to be a good indicator of CFIUS non-notified risk. FIRRMA and its implementing regulations were intended to give CFIUS authority to review minority ownership stakes in venture-backed US companies, many of which are in their startup phase.

- Because responding to a non-notified CFIUS inquiry can be costly and disruptive, parties should thoughtfully allocate and mitigate risks in advance to the extent possible. In addition to conducting appropriate diligence and securing appropriate CFIUS-specific representations, parties can memorialize their diligence efforts, ensure their ability to enforce limitations on foreign investor information rights and agree to share costs arising from a CFIUS inquiry.

Related Contacts

This content is provided for general informational purposes only, and your access or use of the content does not create an attorney-client relationship between you or your organization and Cooley LLP, Cooley (UK) LLP, or any other affiliated practice or entity (collectively referred to as "Cooley"). By accessing this content, you agree that the information provided does not constitute legal or other professional advice. This content is not a substitute for obtaining legal advice from a qualified attorney licensed in your jurisdiction, and you should not act or refrain from acting based on this content. This content may be changed without notice. It is not guaranteed to be complete, correct or up to date, and it may not reflect the most current legal developments. Prior results do not guarantee a similar outcome. Do not send any confidential information to Cooley, as we do not have any duty to keep any information you provide to us confidential. When advising companies, our attorney-client relationship is with the company, not with any individual. This content may have been generated with the assistance of artificial intelligence (Al) in accordance with our Al Principles, may be considered Attorney Advertising and is subject to our legal notices.