UK Antitrust Enforcer Outlines Growing Concerns for AI Foundation Model Markets

Following an almost yearlong review into artificial intelligence (AI) foundation models, and the publication of its initial report in October 2023, the UK Competition and Markets Authority (CMA) has published an updated report and a fuller technical report, outlining its growing concerns that competition in AI is not working as it should. In a speech delivered 11 April 2024, CMA CEO Sarah Cardell further announced that the CMA is commencing a program of work in the space.

We have summarized the key concerns identified by the CMA below, together with a summary of the principles that the CMA encourages AI companies to adopt in their business practices. We expect that the CMA will be markedly stepping up its activity in this space, making use of the full regulatory toolbox – stretching from merger control and competition to consumer enforcement actions, market investigations and digital regulation. We also expect that the CMA’s report will serve as a precursor to increased scrutiny and enforcement activities from European Union (EU) and US agencies.

AI partnerships and ‘acqui-hires’ move into the CMA’s spotlight

The CMA’s findings

In its report, the CMA identified a web of partnerships and strategic investments (including so-called acqui-hires, where the main focus of an acquisition is to acquire talent) within the foundation AI chain involving digital firms, which the CMA believes already have strong positions in critical inputs for foundation model development and/or key access points or routes to market for foundation model release and deployment. The CMA has noted that these partnerships and investments result in deepened relationships among firms at different levels of the AI supply chain, and that they may entail direct financial investment and provision of key inputs, such as data or compute, as well as distribution agreements on an exclusive or priority basis.

The CMA is concerned that these partnerships may allow these large digital firms to exert control and influence over multiple parts of the AI value chain and entrench what the CMA believes is an already strong market position (or extend this into new adjacent markets). The updated report also observes the possibility that incumbent firms may try to use such partnerships to quash competitive threats. In this context, the CMA has noted that it could be particularly concerned if a partnership has one or more of the following features:

- Either party has existing power upstream over a critical input in AI development and/or existing power downstream where the models might be deployed.

- The models involved have significant future potential.

- Either party gains influence over the other’s development of models and/or deployment downstream, especially where there is information exchange and scope to align on incentives.

Noting its concern that some investments may have been structured to avoid merger control rules, the CMA has announced that it will step up the use of its merger control powers to assess whether such partnerships (and potentially also acqui-hires) can be categorized as ‘mergers’, and if so, whether they give rise to competition concerns. Other agencies can be expected to do the same or use other available tools to conduct reviews.

The CMA has materially sharpened its tone with regards to relationships within the AI stack, but what is notable from the updated report is the limited recognition by the CMA of the wider investment context. The CMA makes only a passing comment that partnerships are a necessary part of the investment ecosystem and can bring pro-competitive benefits, but does not explore these issues further.

What does this mean?

The CMA states in its report that it is tracking some of the most significant partnerships (more than 90) in the sector using publicly available information, explaining that it has looked at investments both with and without an equity stake. A number of these partnerships and parties are clearly identified in the CMA’s report. It is to be expected that they will now keep these under close and constant review, and the companies involved shall need to be mindful of this.

In general terms, we can expect significantly enhanced monitoring by the CMA’s merger intelligence team of non-notified acquisitions and strategic investments in the sector. Dealmakers in the AI space should be aware of potential CMA scrutiny of investments and acquisitions, even where those investments may be limited and/or where the normal merger thresholds are not met. The CMA has broad flexibility to intervene in investments. All that is needed to trigger the UK merger control framework is the acquisition of ‘material influence’ which can result not only from a small minority investment, but also from board representation rights, as well as commercial or financial arrangements between companies. Other jurisdictions have similar powers to assess below threshold mergers. Where merger control powers cannot be invoked, we anticipate the CMA and other regulators will look to examine partnership-type agreements under the normal competition law framework for assessing agreements.

Therefore, while we expect that investment into the AI segment will remain vibrant, companies seeking funding or contemplating a strategic investment should conduct a regulatory risk assessment early and consider whether the deal’s characteristics are likely to pique the interests of European regulators, particularly those with more flexible jurisdictional requirements, such as the EU, Germany, Austria and the UK. The outcome of this assessment also should be reflected in the risk allocation provisions of the transaction documents. In conducting this assessment, it will be important to consider the rationale of the partnership or transaction; if scrutinized by regulators, it will be critical that the pro-competitive effects of the investment are clearly articulated.

Dealmakers also will have to remain cognizant of the evolving substantive trends and be aware that the CMA and other regulators will continue to consider the competitive impact of a ‘merger’ on a long-term time horizon, potentially stretching many years into the future. Such an analysis will typically involve a close examination of internal documents – in particular, any discussions of the deal rationale or a party’s future plans in the relevant sector.

Regulating critical inputs and the impact of the AI ‘talent wars’

The CMA’s findings

The updated CMA report also expresses a concern that a small number of large digital firms control critical inputs – such as compute, data and employee expertise – for AI foundation model development. The CMA believes that these large digital firms may be able to use this control to restrict access and prevent challengers from building effective competing models. In addition, the report sets out that some of these firms have strong positions in one or more critical inputs for upstream model development, while also controlling key access points or routes to market for downstream deployment.

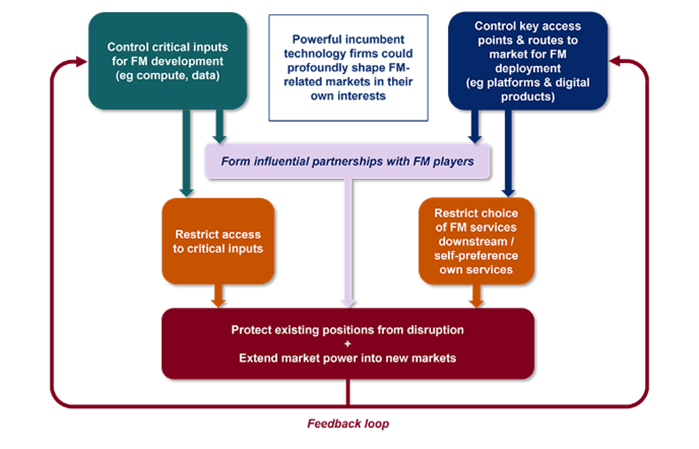

The CMA believes that this creates a particular risk that large digital firms could leverage power up and down the value chain and extend this into new markets. The CMA has illustrated how these concerns might materialize in the following graphic:

Source: CMA

In this context, the CMA has specifically highlighted t ongoing ‘AI talent wars’ and their potential impact on competition. The updated report specifically characterizes AI technical expertise as a key input for building competitive AI models and notes that large technology companies will typically have greater means of attracting and retaining key AI researchers and engineers.

What does this mean?

In addition to its merger control powers, we expect that the CMA will make use of its full range of tools to address its perceived concerns. In particular, the CMA already announced that it would expand its ongoing cloud computing market investigation to include a forward-looking assessment of the potential impact of AI foundation models on competition in the provision of cloud services.

Further, the incoming Digital Markets, Competition and Consumers Bill (see our April 2023 alert) will allow the CMA to designate certain digital companies as having strategic market status (SMS), with each designated SMS firm subject to its own bespoke set of regulatory obligations, including potentially on AI.

With ongoing CMA investigations covering labor market issues and no-poach agreements, further enforcement action involving access to talent in the AI space also is not off the table. Companies in the sector can expect increased scrutiny of nonsolicitation and noncompete restrictions affecting employees.

We also expect that the CMA will seek to cooperate with its counterparts in the EU and US, and that enforcement action in the AI space will be characterized by cross-agency alignment. For example, beyond enforcement of the EU’s general antitrust rules, the top antitrust official at the European Commission’s Directorate-General for Competition, Olivier Guersent, recently said that the EU’s new Digital Markets Act would take into account the impact of AI on the designated core service of a gatekeeper and hinted that the EU may impose interim measures to freeze developments where anti-competitive conduct is suspected. In the US, the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) has launched an inquiry to ‘scrutinize corporate partnerships and investments with AI providers’, with FTC Chair Lina Khan publicly committing not to permit a handful of firms to concentrate control over key AI tools. The Department of Justice also has recently launched an AI initiative and announced its intent to pursue harsher penalties for AI-facilitated crimes.

Consumer choices and consumer enforcement

The CMA’s findings

While the CMA acknowledges that AI foundation models may benefit consumers by providing higher-quality, lower-priced, and more personalized products and services, the CMA believes that there are several consumer-specific risks in the current landscape. For one, the updated report is concerned that choices of people and businesses would be shaped by current familiarity or preference for digital products and platforms, like mobile, search engines, productivity software or cloud-based developer platforms, and that a small number of large firms could use their strong positions in those consumer- and business-facing markets to control how AI models are deployed and what choices are available to customers. In addition, the CMA is concerned that AI models have the potential to facilitate unfair consumer practices, such as subscription traps, hidden advertising and fake reviews.

What does this mean?

Whilst the CMA’s competition law powers will clearly be an important focus in its regulatory approach to AI, we anticipate that exercising its consumer powers will be an equally important priority for the CMA. In this context, the Digital Markets, Competition and Consumers Bill, once in force (anticipated to be later in 2024), will grant the CMA extensive new enforcement powers for breaches of consumer protection law, including the imposition of fines. Importantly, the bill will give the CMA the flexibility to choose whether to use its existing competition law powers, its digital regulation powers and/or its consumer law enforcement powers to tackle any consumer issues it identifies in relation to AI foundation models.

In a shifting technical and regulatory landscape, companies with consumer-facing AI UK activities should therefore ensure that their compliance processes are both robust and adaptable. Importantly, any regulatory assessment of proposed strategies should place equal weight on both competition and consumer impacts, and those risks should be considered holistically.

The CMA’s AI principles

The CMA’s findings

In its 2023 report, the CMA put forward draft principles for companies in the AI sector to adopt when designing business practices and commercial strategies. Having undertaken significant engagement with the sector, the CMA has finalized these. These principles, designed to ensure ‘positive market outcomes’ and effective competition, are as follows:

- Ongoing ready access to inputs.

- Sustained diversity of business models and model types.

- Sufficient choice for businesses and consumers, so they can decide how to use foundation models.

- Fair dealing and no anti-competitive conduct.

- Transparency so that consumers and businesses have the right information about the risks and limitations of foundation models.

- Accountability by foundation model developers and deployers to foster the development of a competitive market.

Further detail of what each of these means is provided by the CMA in its report.

What does this mean?

Whilst the above principles are not mandatory, the CMA calls on companies in the AI sector to align their business practices with these principles. Thus, in articulating how they expect markets and companies to operate, we expect these will be used by the CMA as a yardstick against which the behavior and performance of AI companies will be measured in any enforcement actions and market reviews. In practical terms, AI companies are therefore advised to look to these principles when planning and executing commercial strategies.

Next steps

The CMA expects to take several further steps off the back of this updated report:

- The CMA will likely step up its monitoring and investigating of AI partnerships and acqui-hire deals involving large digital firms.

- The CMA has announced that it will examine the competitive landscape in AI accelerator chips as part of its next phase of its review of the industry.

- The CMA’s ongoing review of the cloud infrastructure sector will be expanded to consider the potential impact of AI foundation models on how competition works in the provision of cloud services.

- The CMA will likely use the powers given to it by the upcoming Digital Markets, Competition and Consumers Bill to ‘designate’ key AI players as having ‘SMS’ – giving the CMA very broad powers to regulate their conduct and activities in the market.

- Together with several other UK regulators (including the UK’s data protection regulator), the CMA will conduct further research on consumer understanding in the use of AI foundation model services, along with issuing a joint statement on the interaction among competition, consumer protection and data protection in AI foundation models.

This content is provided for general informational purposes only, and your access or use of the content does not create an attorney-client relationship between you or your organization and Cooley LLP, Cooley (UK) LLP, or any other affiliated practice or entity (collectively referred to as “Cooley”). By accessing this content, you agree that the information provided does not constitute legal or other professional advice. This content is not a substitute for obtaining legal advice from a qualified attorney licensed in your jurisdiction and you should not act or refrain from acting based on this content. This content may be changed without notice. It is not guaranteed to be complete, correct or up to date, and it may not reflect the most current legal developments. Prior results do not guarantee a similar outcome. Do not send any confidential information to Cooley, as we do not have any duty to keep any information you provide to us confidential. This content may be considered Attorney Advertising and is subject to our legal notices.